A Brief History

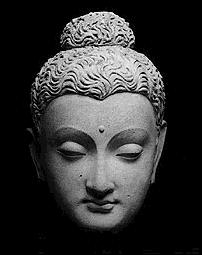

Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, lived approximately two thousand five hundred years ago in the North of India (today Nepal).

As a young man he became very concerned about the fact that everyone was subject to sickness, old age and death. He wondered whether there was release from these three conditions and became determined to find it if there was.

For six years he practiced the traditional life of a wandering ascetic, but did not find the answer. Finally he looked for the answer within himself. It was at this time that he realized freedom from birth, decay and death (deathlessness) an became the Buddha, the fully awakened one.

How Life Is Distorted According to Our State of Mind

For the next forty-five years the Buddha devoted himself to pointing out this way of freedom so that others might also realize it. He taught how life is distorted according to our state of mind; how any kind of worry, fear, grief, wish or hope will distort life.

All of us can easily see this for ourselves. When we are worried, for example, the whole of life takes on a worried appearance; he walls of the room we are in, grass, trees, and whatever we see will all be distorted by our worry. The same is true of despair, anger or any emotion. Life is like a mirror and whatever is in the mind is like an object placed before the mirror. If an angry thought is in the mind, life will reflect that anger and we will see anger wherever we look. There is an old saying, for instance, in India: “A pickpocket who meets a saint will see only the pocket.” But anger is not in the world or in other people; it is in our own minds. The Buddha aw that the same principle also applied to birth, old age and death; that birth old age and death are ideas in the mind. He advised all of us to see ourselves as we really are; to be totally honest about the way we act, speak and think, so that we come to realize how we distort truth by our own states of mind.

If we take this advice, we too will notice this happening in ourselves. We shall realize that everyone sees life according to his own state of mind, and we shall understand that this is the reason people have differing views and opinions. Truth, however, is free of views and opinions. And the way to see truth is to be aware of life as it is. When we know we are coloring a situation with emotion, views or opinions, and acknowledge: “This is an idea. This is emotion, etc, and then abandon those emotions and ideas by just letting them go, a dramatic change will occur in our lives, a change we will be grateful for. There is a saying:

Knowing others is knowledge;

Knowing one’s self is wisdom.

Those who make the effort to discover the way that is free of all suffering and then follow that way, will realize true liberation (deathlessness). But we ourselves must make the effort; Buddhas (there are many, including your own self) merely point the way. And the effort involved is the effort to be aware of these things for ourselves, rather than just believing in them.

Treading the Buddhist Path

Buddhism is based n learning how to stand firmly on one’s own two feet; on how to be very clear about which direction to make in life; about how to conduct oneself, what to say and what to do. This is called treading the Buddhist Path. This Path cannot be presented in a dogmatic way because it is individual to each and every one of us. But there are guidelines laid down by the Buddha on how to realize utter and total freedom from suffering.

Four Noble Truths

We’re dealing here with translations coupled with personal attitudes, but in some circles the four are:

1. Life is dukkha. No single English word adequately captures the full depth, range, and subtlety of the crucial Pali term dukkha. Over the years, many translations of the word (most poorly as “suffering” which puts a shallow and wrong-headed slant to understanding Buddhism) have been used, such as”stress,” “unsatisfactoriness,” the aforementioned “suffering,” etc.).

2. Attachment is the cause of suffering.

3. Non-attachment is freedom from suffering.

4. The Eightfold Path is the way of life which is free of suffering. (More detail on the actual path itself in just a moment.)

More or less, the four Truths listed above are traditional and while not necessarily they are often filtered through poor translations and understandings which, when one views the vast realm of Buddhist teachings, might reflect a particular angle which they can be viewed from. I would like to take a moment, however, to take a view from a different and I think more accurate angle.

A word, first. Put simply, let us start with the idea that it is not what happens to us that causes us to feel things such as anger or despair and so forth but, rather, what we THINK about what happens to us. Keep in mind what was mentioned above about our built-in distortion filters. But let us look at it in a practical sense. Let’s say that at point A a loved one leaves us. At point C, we are depressed and may find our life goes completely off the tracks. In our normal way of doing things, we often assume that A CAUSED C. In other words, we might say: “My girlfriend or boyfriend left me and THAT event made me depressed.” From this, what the Buddha is suggesting is that it not a direct cause and effect relationship between A to C. Most importantly, if we look we can see that in between A and C is actually a point B, our Belief about A. “I am depressed because I wanted the relationship to be unending love” or “My life is now horribly ruined and I am a horrible person who does not deserve to be loved!” That is taking the situation in life to the wall, as it were, and to that we might add: “Things should be the way I want them to be. They should NOT be the way I don’t want them to be!” It is clear that is Point B in which our attitude or vision of demands give rise to the birth of C where, in this case, C is the depression, anger, hatred or meanness we aim at our self or the another.

Perhaps it would be wise to take a look a little more deeply. If, as many of the translations of the Four Truths say, our misery/suffering/bitterness is caused when Attachment is the problem, the obvious question is, “Attachment to what?” I would suggest that we have incorrectly assumed that the answer is “Attachment is when you give a damn about things

or people in life.” But, again, this is not a helpful or an accurate view. The simple fact is that we, as humans, are prone to and eager to build CONCEPTS about ourselves and the world, becoming strong beliefs enshrined as the way things SHOULD be, all of this happening at the expense of seeing things as they really are. Our reactions in life are then far less about a particular item or lover and are more along the lines of reacting to our concepts. I would suggest that, left to our own innate devices, we see the world through distorting lenses of our own making. What the Four Noble Truths do is to give voice to this situation and, quite simply, suggest the real solution is to take off the glasses and, perhaps, make an appointment with another Eye Doctor. In this case the Buddha is that doctor you might want to investigate. To summarize, the answer of attachment and the unsatisfactory nature of one’s life is found in the real framing of the question of “Attachment to what?” It is the attachment to our personally scripted and defended likes and dislikes, hates and loves, prejudices and bigotry which we cheerfully (ha) make the mistake of taking to be Reality itself. Is the argument not with your wife or husband, but are you shadowboxing with what you THINK about the other person and how you THINK the world is somehow magically constructed to bring you frustrations?

To explain further, one of my favorite book titles in Buddhism is Steve Hagen’s Buddhism: It’s Not What You Think. It’s kind of a delightful pun — on the obvious level, it recognizes that some people have the wrong concept of what Buddhism is and isn’t. But, more deeply, ironically it portrays a much more simple truth: Buddhism’s starting message is that what you THINK about the world and the Reality around you on one hand and, on the other, what you see without those distorting lenses are two very different things. Buddhism regrounds your prescription. It says, basically, that you are standing in your own way.

The Four Noble Truths, then, are not grave pessimistic claptrap based on the angst of how life is nothing but suffering (which, of course, it isn’t) and they are not suggesting you have to just stop giving a damn and become stoic and you’ll feel better. That, alas, was how most of the first books in English treated and presented Buddhism at its core which is just not true and not the intention or spirit-in-action of Buddhism in the real world. It often attracted people with a bent toward some measure gloom, but watching the Dalai Lama or Thich Nhat Hahn or any number of teachers in action, one is never left with that impression. Quite the opposite, the key is not being a robot but, rather, the power of involvement with compassion for one’s person as well as the personhood of others who, after all, are traveling in the same boat.

Throughout his teaching career, the Buddha had the unique ability to tailor his teachings to fit the needs and point of view of his listeners. Some of those listening were ripe, as it were, and others were fairly shallow in experience and understanding. The Noble Eightfold Path, like the Four Noble Truths, have their own misunderstandings or slants, so next it is well worth investigating.

The good news about the Four Noble Truths and of Buddhism is that life is sometimes quite bitter. Fortunately, there is a way to remove the bitterness (suffering, if you will). Are you willing to get out of your own way?

The solution suggested has become known, in part, as the Noble Eightfold Path. That investigation continues by mousing over the Buddhism 101 box at the top and selecting Page 2 (Buddhism 101b) from the drop-down menu.